Read: Part 1: Start with Why , Part 2: Making Materials without Going Insane, Part 3: Putting it into Practice and/or Classroom Routines: You will metacognate for background

Consideration 1: Why I love it…

- Having a routine buffers the chaos at the start of class, and buys me a few minutes to deal with whatever needs dealing with that day (a student back from an absence, a message from the counselor, laying out materials for an activity) while students are getting to the work of learning. If it were not this, I am now sold on some consistent ‘do now’ activity.

- Retention – My students’ learning never gets more than a week or two from the top of their minds, and this really does seem to help them retain what they’ve learned. (yay!) This has the side benefit of dramatically reducing frustration, and boosting their sense of competence as math learners. (double and triple yay!)

- It makes me feel better when a student doesn’t totally grasp something in class. We’re not moving on and leaving them in the dust, they’ll see and try it (and get to ask questions about it) again and again and again until they get it.

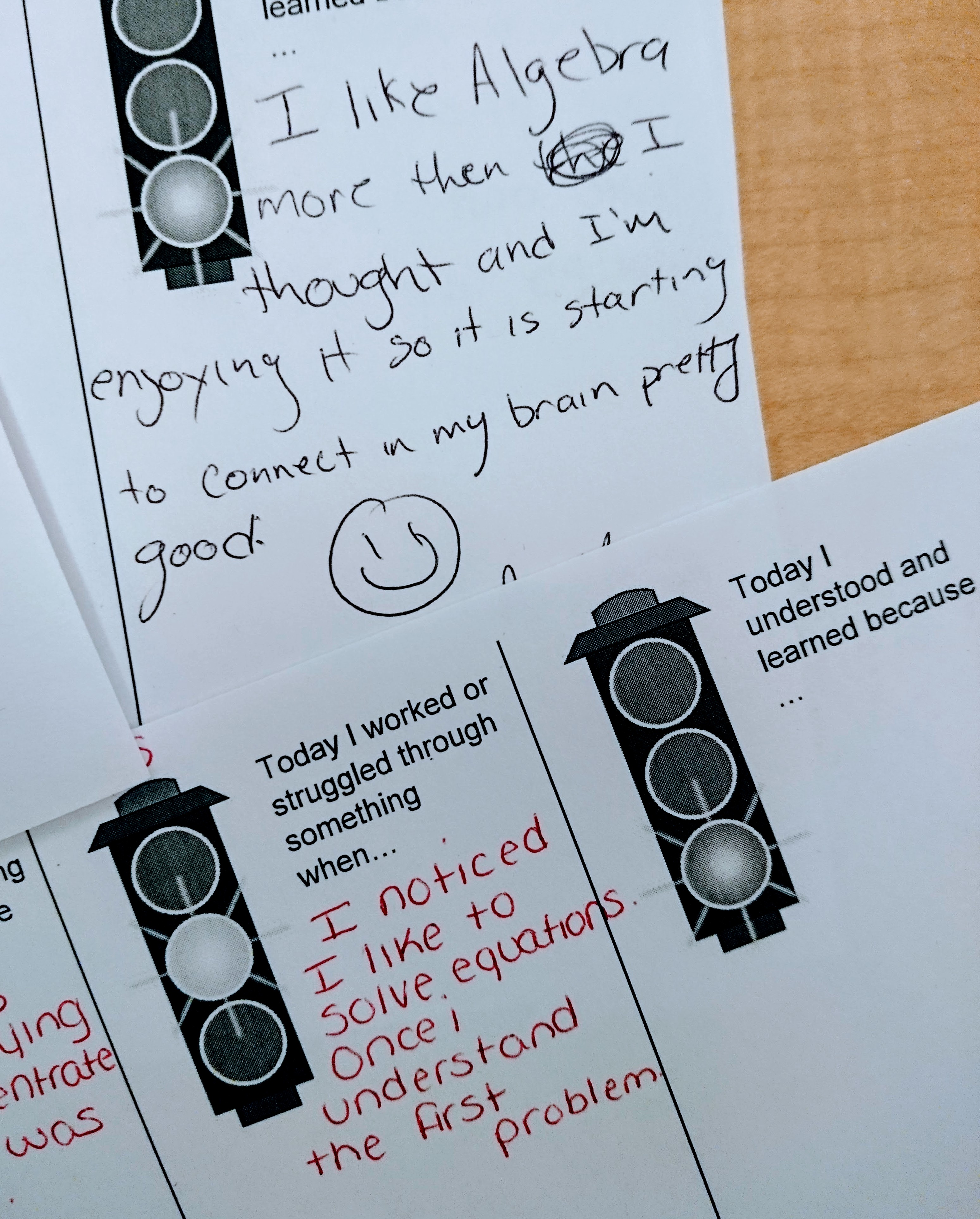

- The metacognitive elements, but especially students taking ownership – correcting, commenting, choosing independent work

- All the good brain science (more on that below)

Consideration 2: But, the time!

I love this system, but, nothing is without trade-off’s. And the big trade-off here is that I devote a lot of class time to this.

The whole routine takes about 30 minutes (out of a two hour class) It could be less, but a) the hazards of teaching adults with jobs/kids/broken down cars include someone straggling in late b) I time it by watching my slowest students c) we’re doing a lot during this time.

(Although, also, I imagine that a K12 class might need less time)

For me, the returns in the form of learning are high enough that I’d do it anyways, but I have also learned that we do get some of that time back at a few points:

-Those all-review days– before the test, at the end of the year, at the end of the term etc. – because we’re reviewing as we go, I can have a ‘real’ lesson on those days.

-Some of the time I’d spend on “Ok class, who remembers what we did last time…?” *crickets* Because we’ve just done a review, I can get to the new stuff faster. (Having the review at the start of class is also a great activator)

-Some of the time I’d spend catching up lost students, or those who take longer, or who had it but forgot, or who just haven’t grasped that one. specific. thing. They’ll get to work on whatever that stuck point is, as part of the regular flow of class, so we’re not doing (as much) time away from class to address their confusion.

Consideration 3: High impact practices

Yes, time intensive, but worth it to me in part because it folds in so many high impact learning practices.

Retrieval practice (remembering what you learned by quizzing etc. )

(My open notes decision undercuts this a bit but, frankly, most students are not taking great notes so I’m not sure who much help they get and they need the encouragement to take any notes.)

(I’m currently experimenting with a ‘purer’ retrieval practice, adding a question at the end asking them to put away the notes and free write what they remember from the previous class. My template includes versions with and without this)

Spaced repetition (aka distributed practice, the opposite of cramming)

Metacognitive Reflection

Interleaving (Studying a mix of topics)

Differentiation/ Student Choice work

Activating Prior Knowledge

(I also have a hunch that this is a sort of informal exposure therapy for the math and text anxiety that run rampant through my classroom. Face a well-supported, low stakes version every week and eventually it gets normal enough to be a little less scary….? I don’t have the research, except a suggestion in this study, if you know more than me, please comment!)

Consideration 4: Adapting it

Spacing – Perhaps a monthly or bi weekly schedule makes more sense for your class, or maybe you do a (more extensive?) version as a transition between each unit?

Correcting – My classes are ungraded (except for the minor matter of the ultra high stakes high school equivalency exam) Perhaps having students correct themselves wouldn’t work in your school culture. Perhaps you grade them, but maybe pairs exchange papers to correct, or the class reviews results together, or you beat me to the technological punch and use a self-grading quiz program.

Timing – A half hour suits my class, but perhaps you reduce the number of questions, or cut back on the folder comment writing and student choice work to make it quicker. Or, extend it to an occasional full-period activity with more questions and review stations.

Structure – Perhaps this is not your starter, but your end of Friday routine. Perhaps the review sheets go home as homework. Perhaps pairs or teams work together, instead of solo. Maybe the process of reviewing is what matters and you drop the folder writing and/or independent work elements altogether.